Important Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings: Kakunodate’s Historic Samurai District

The streets of the historic samurai district are lined with stately residences that look much as they did 400 years ago when Kakunodate was a castle town. During the Edo period (1603–1867), Kakunodate was divided into neighborhoods organized by social class, rank, and occupation: samurai lived in the northern part of the town closer to the castle, and merchants and artisans were relegated to the outer, southern part of town. Large earthen embankments separated the communities to prevent fires from spreading between them and to serve as an initial defensive structure were the town to be attacked.

Each dwelling in the samurai districts has a front garden and is enclosed by a black wooden fence or hedgerow. The fences and hedges were a way to show the boundary between private and public. Historically, the fences would have been taller than the height of the average person (then 150 cm), preventing people from seeing inside, but the modern street surface is about 80 centimeters higher than it was in the Edo period. The 11-meter width of the street, however, is the same as when the town was first built.

The townscape was the first site to be designated an Important Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings in 1976. This designation provides financial support for municipal projects, such as restoration work, façade enhancement, and the installation of disaster-prevention facilities to protect historic cities, towns, and villages. Residents of Kakunodate’s 6.9-hectare preservation district may build new, modern buildings so long as they visually match the existing structures. Changes to the interiors of historic residences and the addition of modern amenities are permitted, but altering the exteriors requires prior approval from a designated council.

Six samurai estates are open to the public: the Aoyagi, Ishiguro, Iwahashi, Kawarada, Matsumoto, and Odano residences.

*Please note that some may only be viewed from the outside

Ishiguro Family Residence

Believed to have been built in 1809, the Ishiguro Family Residence is the oldest of the six residences that are open to the public in Kakunodate’s historic samurai district. It is also the only home that is still occupied by the family’s descendants. For this reason, only the historic half of the home is open for public viewing.

The Ishiguro family purchased this residence in 1853 for 7,000 kanmon (or 7 million mon; at the time a carpenter could earn about 430 mon per day) It is a well-preserved example of an upper-class samurai family dwelling, and many of its architectural features reflect the social customs of the time. For example, the home has three different entrances. The entrance that visitors now use was originally reserved for samurai, whereas members of lower classes had to enter through a side door to its right. To the left is another entrance that was used only on special occasions, such as weddings and funerals. In the zashiki, a room designed for entertaining guests, the tatami mats are arranged in parallel so guests could sit side by side without sitting above the gap between the mats. Guests were seated according to rank, with the most eminent guest seated farthest from the door.

History of the Ishiguro Famil

In the 1500s, the Ishiguro samurai family, under Ishiguro Naoyuki (dates unknown), left Etchū Province (now Toyama Prefecture) and moved to Dewa Province (now Akita Prefecture). There Naoyuki established the Kakunodate branch of the Ishiguro family, and his son Naoki (dates unknown) was the first Ishiguro family head to be employed by the Satake-Kita samurai family. The Satake-Kita governed Kakunodate for more than 200 years under the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868).

The Ishiguro oversaw Kakunodate’s finances, serving as accountants, treasurers, and auditors for the Satake-Kita. As a high-ranking family with substantial wealth and landholdings, the Ishiguro were relatively unaffected by the dismantling of the samurai class in the Meiji era (1868–1912). From the late 1800s until the 1950s, the Ishiguro rented land to tenant farmers in exchange for a percentage of the annual rice yield.

Many of the Ishiguro were well versed not only in martial arts, but in other subjects such as Confucianism, the Chinese classics, mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. Members of the samurai class often studied medicine to aid themselves during war, famine, and other times of crisis. The Ishiguro collected books on anatomy and medicine, which they used to diagnose illnesses and provide medical treatment to nearby residents. A descendant of the Ishiguro, Takahashi Kyūzaburō (dates unknown), was the first doctor to introduce the smallpox vaccine to Akita Prefecture.

- Open

- 9 AM to 5 PM

Open throughout the year

- Charge

- Adults/High School Students 400 yen, Elementary/Junior High School Students 200 yen

In groups of 20 people or more: Adults/High School Students 300 yen, Elementary/Junior High School Students 150 yen - Location

- 1, Omotemachishimocho, Kakunodate

- Contact Info

- Ishiguro House: 0187-55-1496

- Traffic access

- Twenty minutes on foot from JR Kakunodate Station

Aoyagi Residence

The Aoyagi residence was built during the Edo period (1603–1867), which was characterized by rigid class stratification. Society was divided into four main classes: samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants, and the design of people’s homes reflected their social status. Based purely on the architectural features of the Aoyagi residence, historians have determined that they were upper-ranking samurai.

Farmers were only permitted to build single-story houses with thatched roofs, and they were not permitted to have front gates or entrance halls. Merchant houses were two-story structures built close together on small plots of land with narrow front entrances that opened onto the street. Samurai residences, however, were typically built on larger plots of land with impressive front gates and entrances that reflected each family’s specific rank. The Aoyagi estate occupies just under 1 hectare of land (about the size of an international rugby field) and has a formal yakuimon-style gate built by master carpenter Shibata Iwatarō (dates unknown) in 1860. The family could only build this style of gate with special permission from the domain, as it was a prestigious symbol of a family’s social standing. The gate has a gabled roof and decorative metal fittings.

On the lefthand side of the gate are slightly protruding “warrior windows” (mushamado) that allowed people inside to look outside without being seen. The front entrance hall was built with low ceilings so that potential assassins could not easily swing their swords, and the latticed interior windows allowed the family to see guests before they entered the main home. These defensive features, combined with a hidden staircase to a room on the second floor, attest to the Aoyagi family’s position as guardians of the border between what are now Akita and Iwate Prefectures.

History of the Aoyagi Family

During the late sixteenth century, the Aoyagi family were retainers of the Ashina family. The Ashina served the Satake, a family of daimyo who governed Hitachi Province (now part of Ibaraki Prefecture). In 1602, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), who the following year would take control of all of Japan as the first Tokugawa shogun, forced the Satake to relocate to Akita domain (now part of Akita Prefecture). The Ashina followed their lord to Akita, and the Aoyagi went with them.

The Ashina governed the castle town of Kakunodate until 1656, when the Satake-Kita branch of the Satake family was reassigned there. Under the Satake-Kita, the Aoyagi led the border guards between what are now Akita and Iwate Prefectures. The family held this position for over 200 years. In 1860, the Aoyagi family was permitted to build an elaborate yakuimon-style front gate as a reward for their years of service to Akita domain. This gate was the pride of the Aoyagi family as a symbol of their social standing and prestige.

When the Aoyagi first arrived in Kakunodate, they were a middle-ranking samurai family with a yearly stipend of between 45 and 60 koku of rice. A koku is approximately a year’s worth of rice for an adult person (about 150 kg) and was the standard unit of payment for samurai. By the end of the Edo period (1603–1867), however, the Aoyagi took in 200 koku each year, partially due to land acquisitions over the two and half centuries of peace. This financial success allowed the Aoyagi to thrive during the following decades of rapid industrialization, even as the samurai class was abolished and most other samurai families fell into poverty or were forced to sell their estates.

- Open

-

(April to November) 8:30 AM to 5 PM

(December to March) 9 AM to 4 PM

Open throughout the year - Charge

- Adults 500 yen, Junior High/High School Students 300 yen, Elementary School Students 200 yen

In groups of 20 people of more, Adults 450 yen, Junior High/High School Students 250 yen, Elementary School Students 150 yen - Location

- 26, Higashikatsurakucho, Kakunodate

- Contact Info

- Aoyagi House: 0187-53-2006

- Traffic access

- Twenty minutes on foot from JR Kakunodate Station

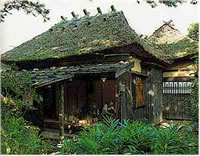

Former Residence of the Matsumoto Family

The Matsumoto residence is a rare example of a lower-class samurai house from the Edo period (1603–1867). Within Edo society, the quality of life between high-level and low-level samurai was very different. High-ranking samurai directly served the daimyo and were often wealthy enough to afford their own retainers. Low-ranking samurai, however, were paid very little and typically worked as guards, messengers, or simple clerks. Castle towns were arranged with the highest-ranking families closest to the castle, and each family’s rank determined the designs and materials they could use to build their residences.

Located in the Kobitomachi district, the Matsumoto residence occupies a plot of land that was small by samurai standards. It lacks a formal gate and does not have the black-painted fences that are characteristics of Kakunodate’s upper-class samurai district. Instead, it has two wooden poles and a humble brushwood fence. The thatch-roofed main building has a floorplan of around 91 square meters. Visitors to the residence would enter the living room via a small annex that connects to the zashiki, a room for entertaining guests. This annex has an awning made of cedar bark shingles weighed down with stones. An addition at the back of the home was originally where the family slept.

Today, the Matsumoto residence is used to hold live demonstrations of itayazaiku, a 200-year-old folkcraft that involves weaving strips of Itaya maple (Acer mono) bark into baskets, boxes, and other objects. Itayazaiku and other handicrafts were an important source of additional income for low-ranking samurai in Kakunodate.

History of the Matsumoto Family

The Matsumoto were a well-educated but low-ranking samurai family that originated in Hitachi Province (now part of Ibaraki Prefecture). They came to Kakunodate in the early Edo period (1603–1867) as retainers of the Imamiya, a family who were responsible for overseeing the practice of Shugendō, an ascetic mountain faith.

When the Matsumoto first arrived in Kakunodate, they lived alongside other retainers of the Imamiya family in the Tamachi area of town. However, control of the castle town was later ceded to the Satake-Kita family, and the Imamiya were sent to a different part of Akita, leaving their retainers to work for the new lords. Accordingly, the Matsumoto were reassigned to serve the Satake-Kita and, like most other samurai families, moved to districts of Kakunodate that corresponded with their rank, wages, and/or affiliation. Today, the Matsumoto residence is in Kobitomachi, where the low-ranking attendants (kobito) tasked with miscellaneous duties, such as delivering messages and transporting supplies, lived.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, lower-class children were able to obtain a basic education at terakoya, or “temple schools.” Terakoya were organized by Buddhist temples and held classes in private homes in the community. Their primary purpose was to teach children to read and write. Sudō Hangoro (1775–1851), a member of the Matsumoto family, taught at a terakoya in Kakunodate and even developed his own textbook, the Ebōshioya. This reader covered a wide range of subjects and was designed to be easy to memorize. It contained basic knowledge for everyday life, including geography, history, culture, social etiquette, and cooking. Today, the textbook provides an illuminating glimpse into Kakunodate’s past.

- Location

- Kobitomachi, Kakunodate

- Contact Info

- Semboku City Industry and Tourism Department Tourism Section: 0187-43-3352

- Traffic access

- Twenty minutes on foot from JR Kakunodate Station

Iwahashi Residence

The Iwahashi residence is an excellent example of how traditional Japanese houses were built to protect their occupants from natural disasters. It is earthquake-resistant: the central, weight-bearing pillars are placed on rounded stones allowing them to sway with the tremors. The residence is one of only two buildings in east Katsurakuchō to survive the fire of 1900. This is thought to be because it was roofed with wooden shingles rather than thatch. Shingles are less likely to catch fire due to their smaller surface area and greater water retention.

The Iwahashi residence has four main rooms: the entryway (genkan), the sitting room (zashiki), the room where the master of the house resided (okami), and a storage room (nando). The genkan is the main entryway to the home and is divided into an entrance for guests and an entrance used by the family. The guest entrance is connected to the formal sitting room for entertaining guests, which is enclosed by sliding doors and faces the garden. Notably, while most other samurai homes in Kakunodate have roofed outer corridors with storm shutters, the Iwahashi residence has an open corridor that wraps around the outside of the home.

The okami is centrally located so that the master of the house could see into every room, including the front entrance. It was well decorated compared to the main living area. The main living area is situated in the rear half of the home, as is the nando, where the family’s clothes and other valuables were kept. In this manner, the Iwahashi family could separate their private lives from their public lives, which was required by the class-based society of the Edo period (1603–1867).

History of the Iwahashi Family

The Iwahashi were a middle-class samurai family from Aizu, Mutsu Province (now part of Fukushima Prefecture). Iwahashi samurai were known for their skill on the battlefield and received many accolades for their contributions to military campaigns between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. The earliest record of the family is a letter addressed to Iwahashi Yaemon (dates unknown) commending him for his distinguished service at the Battle of Numajiri in 1584.

The Iwahashi were originally retainers of the Ashina, a samurai family who governed Aizu domain for four centuries. When the Ashina suffered a devastating loss against the powerful samurai leader Date Masamune (1567–1636) in 1589, they fled to Hitachi Province (now part of Ibaraki Prefecture) to seek the support of Satake Yoshinobu (1570–1633), a close relative. Later, the Iwahashi family bid farewell to their home in Aizu and followed the Ashina to Hitachi. However, it was not long before tragedy struck, and a bloody dispute forced the Iwahashi to flee and find a new lord.

The Iwahashi wandered from Edosaki to Iwaki to Edo to Hirosaki, seeking employment under different lords in northeastern Honshu until Iwahashi Mataemon (d. 1651) settled in Akita’s Kakunodate. There, Mataemon served the Iwahashi’s former masters, the Ashina, until a series of untimely deaths ended the Ashina family bloodline. Although committing ritual suicide, or seppuku, had been strictly forbidden, Mataemon chose to follow his lord to the grave. The other retainers were moved by Mataemon’s sheer determination to uphold his honor, and the rest of the Iwahashi family were permitted to go unpunished, despite his actions.

For the next 200 years, the Iwahashi remained in Kakunodate and served the Satake-Kita family, who replaced the Ashina. When the samurai class was dismantled in the early Meiji era (1868–1912), the Iwahashi lost their samurai status, but were able to maintain their place in Kakunodate society by adopting a son from the wealthy Nishinomiya family.

- Open

- Mid-April to Novemeber

9 AM to 4:30 PM - Charge

- Free

- Location

- Higashikatsurakucho, Kakunodate

- Contact Info

- Semboku City Board of Education, Cultural Assets Section : 0187-43-3384

- Traffic access

- Fifteen minutes on foot from JR Kakunodate Station

Kawarada Residence

The Kawarada Residence’s main building is around 130 years old, but the yakuimon-style gate is much older and is believed to have been relocated from the Kawarada family’s former home. Under the social class system of the Edo period (1603–1867), certain architectural features, such as gates, represented the social standing of each household and were the pride of their respective families. In the 1910s, the Kawarada introduced electricity to Kakunodate and received the city’s first telephone number, which is indicated by a wooden tag attached to the front gate.

The Kawarada residence is one of only two houses in east Katsurakuchō to have survived the fire of 1900. The fire started in lower Kakunodate, where the townspeople and merchants resided, but it ended up jumping the dirt embankment that divided the castle town. Many people came to help extinguish the flames and cover the thatch roof of the Kawarada residence in seaweed to prevent it from catching fire. The original roofing has since been replaced with corrugated metal, but burn marks from the fire can still be seen on the southern side of the home.

The Kawarada family were patrons of the arts, and the front rooms in the home are decorated with hanging scrolls, framed calligraphy, folding screens, and sliding doors with paintings by local artists, such as the father-son painters Hirafuku Suian (1844–1890) and Hyakusui (1877–1933). The formal reception room where the Kawarada entertained guests looks out onto a dry garden of trees, rocks, and moss. The rear section of the home is more modest in comparison, and its rice storehouse has since been converted to display the family’s history and belongings.

History of the Kawarada Family

The Kawarada were an influential family of scholars, politicians, and entrepreneurs who contributed to the development of what is now the city of Senboku. Before moving to Kakunodate, the Kawarada had holdings in eastern Tohoku that they had received from Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147–1199), the first shogun of Japan. However, the Kawarada were eventually defeated by and entered the service of the Ashina family, who oversaw the castle town of Aizu and, later, Kakunodate.

The Kawarada held the post of bantō, or head clerk, of the jisha-bugyō, an office that managed Kakunodate’s temples and shrines. City planning was another duty of the jisha-bugyō, which necessitated a knowledge of East Asian geomancy. The arrangement of buildings in an auspicious manner was believed to ward off misfortune, prevent natural disasters, and suppress disease. Members of the Kawarada family also led the reclamation of the marshland and created private schools that taught literary arts, such as Chinese poetry.

When the samurai class was abolished in the early Meiji era (1868–1912), Kawarada Jiryō (1854–1902) turned the family business toward land acquisition, increasing their financial assets until they were one of the five wealthiest families in Akita Prefecture. Jiryō was elected to the Prefectural Assembly seven times, first at age 26. His successor, Kawarada Jijū (1876–1928), was an entrepreneur who made great contributions to Akita’s agriculture, forestry, and electric power industries. Not only did Jijū open his own agricultural school, but he also consolidated land, maintained irrigation systems, and purchased new farming equipment to increase local crop yields. Jijū later sold most of his assets to establish the Kawarada Hydroelectric Company and bring hydropower to Akita. His power plant began service in 1912 and provided electricity to 1,237 homes in the greater Kakunodate area until the consolidation of electric services in 1972.

- Location

- Higashikatsurakucho, Kakunodate

- Contact Info

- Semboku City Board of Education, Cultural Assets Section : 0187-43-3384

- Traffic access

- Fifteen minutes on foot from JR Kakunodate Station

Odano Residence

The original Odano family residence burned down in the fire of 1900 but was rebuilt the same year with traditional Edo-period architectural features. For example, its gabled roof was covered with multiple layers of thin, wooden shingles. The floorplan also follows a traditional layout that includes a front entrance, upper and lower living rooms, the room where the master of the house resided (okami), a formal room for entertaining guests (zashiki), the room in which the family slept (nakanoma), and a storage room (nando).

In most samurai residences, the main house is just beyond the front gate. However, the main house of the Odano residence is situated nearly 20 meters back from the front gate. The straight path to the doorway is lined with dōdan tsutsuji (Enkianthus perulatus) shrubs. Upon arriving at the residence, guests would enter through one of two doors depending on their rank: the higher-ranking guests through the left and the lower-ranking guests through the right. The left-hand side has a smaller secondary door for servants of high-ranking guests to enter through and announce their arrival.

The Odano family excelled in martial arts and practiced swordsmanship, kyūdō (Japanese archery), spear fighting, and other martial arts. They taught swordsmanship and other martial arts in a dojo at the southwest corner of the residence. The front of the residence is lined with Japanese fir, cedar, maple, and cherry trees. A sea of kuma bamboo grass (Sasa veitchii) surrounds the Odano family shrine, which is dedicated to Inari, the deity of agriculture, industry, and prosperity.

History of the Odano Family

The Odano family traces its lineage back to the Satake family, the governors of Hitachi Province (now part of Ibaraki Prefecture) in eastern Honshu. The family was founded by Odano Yoriyoshi (b. 1411), who governed an area called Odano in what is now part of Hitachiomiya City. Yoriyoshi took his family name from the name of his holdings. The Odano served as high-ranking officers under the Satake and followed them to Akita domain in the early seventeenth century.

The Kakunodate branch of the Odano family were retainers of the Imamiya, direct relatives of the Satake who oversaw practitioners of Shugendō, an ascetic mountain faith. However, when the Kita branch of the Satake family was assigned to govern the castle town of Kakunodate, Shugendō entered the jurisdiction of the jisha-bugyō office that managed temples and shrines, and the Imamiya were transferred to a different part of Akita. The Odano then became retainers to the Satake-Kita family. Under the Satake-Kita they became watchmen: leading border guards and responsible for guarding the domain’s rice storehouse. The Odano also helped to establish a rice delivery route between Kakunodate and the copper mines at Anikōzan via Daigakuno Pass.

Around this time, the scholar and painter Hiraga Gennai (1728–1780) encountered Odano Naotake’s (1750–1780) artwork during a 1773 visit to Akita. Deeply moved, Hiraga met with the young artist and taught him the basics of ranga, or “Dutch-style,” painting, such as the use of shadows and linear perspective. The following year, Naotake illustrated the Kaitai shinsho (New Text on Anatomy), the first translation of a foreign medical text into Japanese, with images of human anatomy drawn in a Western style. He is now known as the founder of the Akita school of ranga painting that blended Japanese- and Chinese-style themes and compositions with Western-style perspective and shading.

- Open

- Mid-April to Novemeber

9 AM to 4:30 PM - Charge

- Free

- Location

- Higashikatsurakucho, Kakunodate

- Contact Info

- Semboku City Board of Education, Cultural Assets Section : 0187-43-3384

- Traffic access

- Fifteen minutes on foot from JR Kakunodate Station

Former Residence of the Ishiguro-Kei Family

This residence was built for a daughter of the Ishiguro family in 1935. Although the building is far more modern than the Edo-period (1603–1867) samurai houses of Kakunodate’s Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings, it is an excellent example of a prewar home that incorporates Western and Japanese architectural elements.

Samurai residences were typically built on a grid-like layout with four rooms of equal size, one of which was dedicated to receiving and entertaining guests. This room had its own entryway through which guests came and left. The family’s living space was located at the back of the home and had its own separate entrance. In contrast, the Ishiguro-Kei residence is not divided into public and private spaces, and its Western-style floorplan has a single front entrance for use by the family, guests, and service workers alike.

The home’s parlor (kyakuma), Western-style living room (ima), Japanese-style living room (chanoma), master bedroom, and children’s room are divided by walls (rather than sliding doors) and connected by indoor hallways. This differs greatly from traditional homes, which feature partitioned tatami rooms and outer corridors that wrap around the entire house. The home’s interior finishings also include both Western and Japanese elements, such as plaster ceilings and bay windows in the drawing room and the sukiya teahouse-style cutout windows that can be found throughout the house.

The Ishiguro-Kei residence was donated to the town of Kakunodate in 1999 by Ishiguro Kei (1929–2005), who had moved with her family to Chiba Prefecture. The residence was restored between 2008 and 2009 and opened to the public in 2010. The house’s roof, foundation, and other damaged sections of the exterior were replaced, but the interior remains nearly untouched, save for the addition of a few modern amenities, such as a kitchen.

History of the Ishiguro-Kei Family

The Ishiguro-Kei were a branch family of the Ishiguro, a samurai family who moved to Kakunodate from Etchū Province (now Toyama Prefecture) in the sixteenth century. For nearly 200 years, the Ishiguro oversaw financial matters in Kakunodate on behalf of the Satake-Kita family, and by the turn of the twentieth century, they had acquired wealth and their own landholdings. The Ishiguro family home still stands opposite the Former Ishiguro-Kei Residence on the corner of Bukeyashiki Street.

The Ishiguro-Kei are close relatives of the Ishiguro family, from whom they separated during the Edo period (1603–1867). In the traditional kinship system, a family consisted of a primary household connected to various branch families via patrilineal kinship. Typically, headship of the principal family was passed down to the eldest son, who inherited the family property and financial assets; younger sons established their own branch families. This required permission from the head of the household, who might provide the new branch family with property if it was not financially independent.

The Ishiguro-Kei branch resided in Kakunodate until Ishiguro Kei (1929–2005) moved to Chiba Prefecture with her family. In 1999, Kei donated her former home to the town of Kakunodate. It is now used as a community center.

- Location

- Higashikatsurakucho, Kakunodate

- Contact Info

- Semboku City Board of Education, Cultural Assets Section : 0187-43-3384

- Traffic access

- Fifteen minutes on foot from JR Kakunodate Station

- Access

- Sightseeing Spots

- Choose from areas

- Hachimantai/Tamagawa

- Nyutou

- Tazawako Plateau/Mizusawa/Komagatake

- Tazawako

- Dakigaeri/Jindai/Shiraiwa

- Nishiki

- Kakunodate

- Seasonal Recomendations

- Lists by Season

- Campgrounds

- Products

- Other